The Kalevala has again become a heated topic in Finland: The European Commission awarded the Kalevala, representing “Karelian and Finnish cultural heritage,” the European Heritage Label in April 2024. However, some Finnish Karelians are claiming the Kalevala as the Karelian national epic and criticizing Elias Lönnrot and Finnish national culture, to which the Kalevala greatly contributed/is contributing, as colonialist and cultural appropriation (As a recent example of this criticism, there was an incident of smudging the Elias Lönnrot statue).

Personally, as a historian of foreign origin in Finland, this topic attracts my interest, since I have just completed my doctoral dissertation on the Kalevala controversy in Soviet Karelia and between Finland and the Soviet Union in the 1940s and 1950s, which I surprisingly and accidentally find very timely and relevant to what is happening today. The Kalevala Society generously offers me an opportunity to introduce my discussion on the Kalevala and Finnic kinship based on my dissertation.

How did I find the Soviet-Finnish Kalevala controversy as a research topic?

My dissertation addresses the Soviet imperial rule in Soviet Karelia through nationalities issues rather than the Kalevala controversy per se. Thus my discussion might be different from the previous studies on the Kalevala which have been previously published: the studies on the Kalevala controversy have focused, among others, on the authenticity of the Kalevala epic poems. Indeed, the works Kalevala maailmalla (edited by Petja Aarnipuu, 2012) and Kalevalan kulttuurihistoria (edited by Ulla Piela et al., 2008) offer some pieces how the Kalevala was received in different national and cultural contexts (the recent project, “Kalevala Around the World,” is another achievement in this context). Still, the Kalevala and the controversy have been discussed strictly within the Finnish national framework in Finnish or at most within a European framework of Romanticism in the 19th century. Recent works by Juha Hurme Kenen Kalevala? (2023) and Markku Nieminen Minun Kalevalani (2023) are efforts to popularize the Kalevala controversy among broader Finnish readers and also spare a few pages to the Kalevala in Soviet Karelia, where the Red Finns and Otto Wille Kuusinen were engaged in the Kalevala.

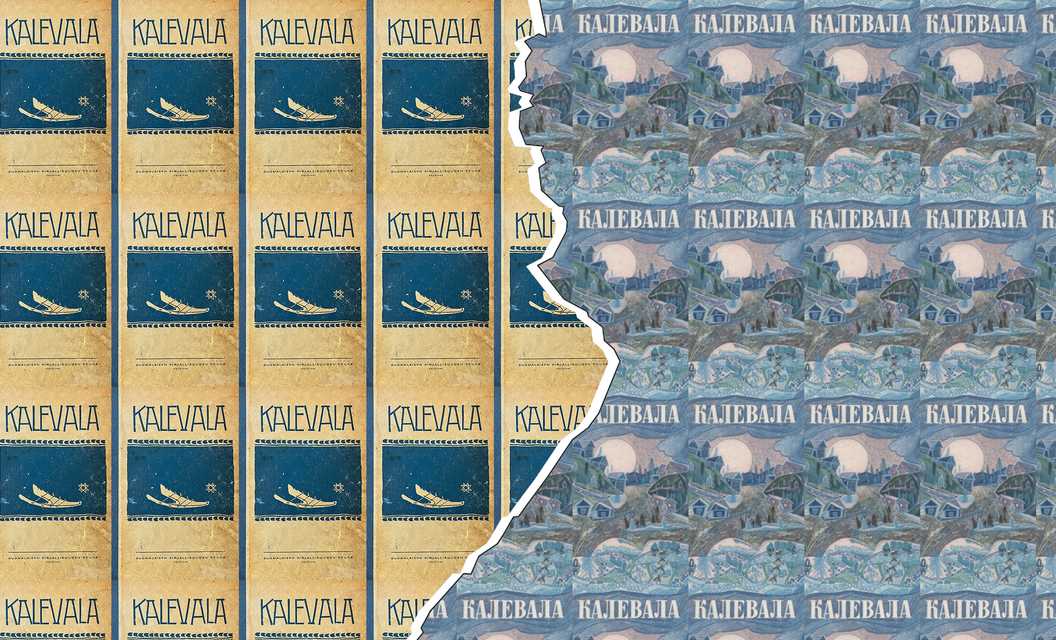

This seemed quite natural: the Kalevala is the Finnish national epic; this is how I learned about the Kalevala and Elias Lönnrot in high school in my Tokyo years, when I came across the Kalevala for the first time. However, as a student in Soviet history, and the history of Soviet Karelia in particular, I found little information about the Kalevala in the Soviet Union at that time. True, the Soviet political and ideological authorities primarily used the Kalevala as a propaganda tool against Finland, especially after they purged the Red Finns who tried to establish another, their own Kalevala (different from the Kalevala in Finland) as a symbol of a socialist Finland and of the world proletariat. Overall, pioneering works on Soviet Karelia by Markku Kangaspuro, who wrote Neuvosto-Karjalan taistelu itsehallinnosta (2000) and by Mikko Ylikangas, whose book was Rivit suoriksi! (2004) addressed, at least partially, the Finno-Karelian kinship and this “Red” or “Red Finnish” Kalevala. After the Soviet Union invaded and annexed parts of Finland in 1939, the Soviet leadership haphazardly set up the new Karelo-Finnish Soviet Republic in Soviet Karelia and started to establish the “Soviet” Kalevala, which is different from the Kalevala in Finland and the Red Kalevala. Regarding this Soviet Kalevala, Timo Vihavainen’s short piece “Kaksi Kalevalan satavuotisjuhlaa” (Kanava, no. 7, 1983) and Osmo Hyytiä’s monograph Karjalais-Suomalainen Neuvostotasavalta 1940–1956 (1999) offer some hints. However, there was little information on the Soviet Kalevala and almost no information on the Soviet-Finnish Kalevala controversy when I began to draft my dissertation on the history of the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Republic from 1940 to 1956. Indeed, the Soviet Kalevala is a propaganda tool from a Finnish perspective, but is it only such a political tool for the Soviet people as well? Obviously, no. How, then, can there be an understanding of the two Kalevalas and this binary opposition, especially during the New Kalevala (1849) centenary in 1949 when the Kalevala controversy was very intense in both Finland and the Soviet Union?

The Soviet Kalevala as a transnational history

Actually, in the Finnish National Library, I discovered a copy of the collected papers from the scholarly session at the Soviet Kalevala centennial jubilee in 1949, which most probably the Soviet Union sent to Finland to demonstrate what the Soviets had achieved. At that time, I knew little about the Kalevala (needless to say, I knew nothing about the Soviet Kalevala!), but I was surprised by the fact that prominent Soviet scholars and writers took part in this jubilee to discuss the Kalevala under the pressure of an anti-Western, Stalinist ideological campaign. In addition, those actors who took part in the Kalevala controversy in the Soviet Union were Soviet citizens in terms of citizenship, but they were Russians, Jews, Germans, Finns (including Ingrian Finns), Karelians, Veps, and Estonians in terms of nationality. Thus, I wondered how this multinational character of the Soviet Union influenced the Soviet perception of the Kalevala. In other words, how did the Soviet imperial rule and ideology inform the Soviet approach to the Kalevala to make it the Soviet Kalevala?

After this discovery, I sought archival documents on this topic in Petrozavodsk, St. Petersburg, Moscow, Tallinn, Tartu, and Berlin and came to a hypothesis that the Soviet Kalevala centenary jubilee in 1949 was a transnational event to perform the Kalevala not only as a Soviet, socialist epic, but also Karelo-Finnish national epic. Various actors in Moscow, Leningrad, Petrozavodsk, Tartu, Tallinn, Berlin, Budapest and in each Soviet republic seriously discussed and discussed competing theories over the Kalevala. Indeed, this jubilee was a farce in a sense, because all the participants praised the Kalevala as the national epic of the Karelo-Finnish people, while they knew that there was only a small number of Finns in Soviet Karelia, because of the Stalinist terror, deportation, wars, and evacuation. Still, the Kalevala as the Karelo-Finnish epic was critical for various actors, including Soviet Finns, Ingrian Finns, Karelians, Veps, Estonians, Germans, and Jews. The Soviet Kalevala was articulated through complicated negotiations within the Soviet Union: In the centenary jubilee, Armenians, Ukrainians, Turkmens, and others associated the Karelo-Finnish national epic with their own national culture.

The Kalevala as a Soviet-Finnish epic

This finding raised another question: Should the Kalevala controversy be interpreted within the Finnish national framework? Was there a Soviet-Finnish dialogue over the Kalevala even in the 1940s and early 1950s, when the Soviet-Finnish borders were almost closed, and communication was very strictly controlled? In fact, Russian archival documents reflect that Otto Wille Kuusinen and other Soviet scholars carefully followed and studied the discussion (even via doctoral dissertations!) on the Kalevala in Finland and articulated their own, Soviet Kalevala vis-à-vis the Finnish Kalevala. Is it possible to reinterpret the Kalevala controversy by regarding the Kalevala as a Soviet-Finnish epic, if Soviet and Finnish scholars followed and tried to understand each other?

These questions encouraged me to extend the transnational framework to the Soviet-Finnish interactions in the late 1940s and early 1950s in order to scrutinize the dialogue on the Kalevala between the Soviets and Finns. For this aim, I reread classic writings on the Kalevala and the controversy by Finnish and (imperial) Russian scholars from the pre-independence time. Indeed, there was a dialogue between imperial Russian, later Soviet, and Finnish scholars: Kaarle Krohn and Alexander Veselovsky and Vladimir Gordlevsky; Dmitry Bubrikh and Paavo Ravila and Lauri Kettunen; Viktor Evseev and Matti Kuusi and Väinö Kaukonen, to name a few. This dialogue does not always mean direct correspondence. Especially Soviet scholars in the late 1940s tried to understand what the Finnish counterparts argued through academic publications, newspaper and journal pieces and even rumors to discuss various issues: where did the Kalevala epic poems appear? Who created the poems? What is the role of Elias Lönnrot in the creation of the Kalevala? This reinterpretation convinces me to argue that the Kalevala could be seen as a Soviet-Finnish epic in this transnational context, neither an exclusively Finnish nor Soviet epic, as my dissertation demonstrates.

One of the advantages this interpretation provides is that it is possible to more clearly the difficult situation in which Soviet Karelians found themselves in the Kalevala controversy and the Finnic language kinship, especially Finnish-Karelian kinship, heimoaate, which I translate as “pan-Finnism” in English, one of the most important issues in the Kalevala controversy. My argument here is that the Soviet Union utilized the pan-Finnism ideology in its rule over Soviet Finnic people after the Second World War, although the Soviet Union (and Russia today) condemned Greater Finland and pan-Finnism. The Bolshevik leadership assigned the Red Finns in Soviet Karelia to implement their plan to build socialism by “Finnisizing” Soviet Karelians while nurturing a Soviet Karelian identity different from Finns and Russians. When Moscow created the Karelo-Finnish Republic and rehabilitated the Finnish, local elites, either Russian or Finnic, thus faced again the Karelian-Finnish kinship through the Kalevala controversy: are Karelians kindred with Finns? Or are they rather close to Russians? Or are they different from both Finns and Russians? The official answer was that Soviet Karelians are the Karelo-Finnish people who were expected to be fluent both in Finnish and in Russian in the Russian-centric Soviet Union.

It was the Livvi Karelian researcher Viktor Evseev who faced these questions. His life and career represent well the Soviet Karelians: he was the first Karelian doctorate in Soviet folkloristics and fluent in both Finnish and Russian, but was proud of his own mother tongue; he sought purely Karelian epic songs and the Kalevala as the “Karelian” epic, but, because he was in Soviet Karelia, had to praise the epic as the Karelo-Finnish epic – not as the “Karelian” epic – and Elias Lönnrot, and write either in Finnish or in Russian, not in Karelian. He was allowed to condemn Greater Finland and Finnish “bourgeois” nationalism, but had to write properly in Finnish and thank the Russian people, the elder brother, and the Communist Party for helping and raising the Karelian people and culture, matured enough to compete with the “bourgeois” Finnish scholars for the Kalevala. In compensation for this, Evseev had to so strictly comply with the official ideological line that some ridiculed his doctoral dissertation as a copy of Otto Wille Kuusinen’s Kalevala. However, at the same time, it was Evseev that played a central role in the Soviet-Finnish dialogue during the New Kalevala centenary in 1949, especially his dialogue with Väinö Kaukonen, who was willing to build a friendly relation with the Soviet Union and who carried out verse studies of the Old and New Kalevala (Kaukonen 1939, 1945, 1956). One of my discoveries is this dialogue on the Kalevala between Evseev and Kaukonen after the Second World War.

My dissertation will not offer direct answers to the Kalevala controversy in Finland today, since it deals with the events in the 1940s and 1950s. However, there were some similarities between what various actors in Finland and the Soviet Union faced in more than half a century ago and what we are facing now. I hope my dissertation offers different angles on the current discussion on the Kalevala and encourages further dialogues and questions in both Finland and Russia.

Takehiro Okabe’s doctoral dissertation is published by Suomen Tiedeseura/The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters. Takehiro Okabe, Taming Greater Finland: Pan-Finnism, the Soviet-Finnish Kalevala Controversy, and the Karelo-Finnish Soviet Republic, 1940–1956. Commentationes Scientiarum Socialium 83 (Helsinki: The Finnish Society of Sciences and Letters, 2024).