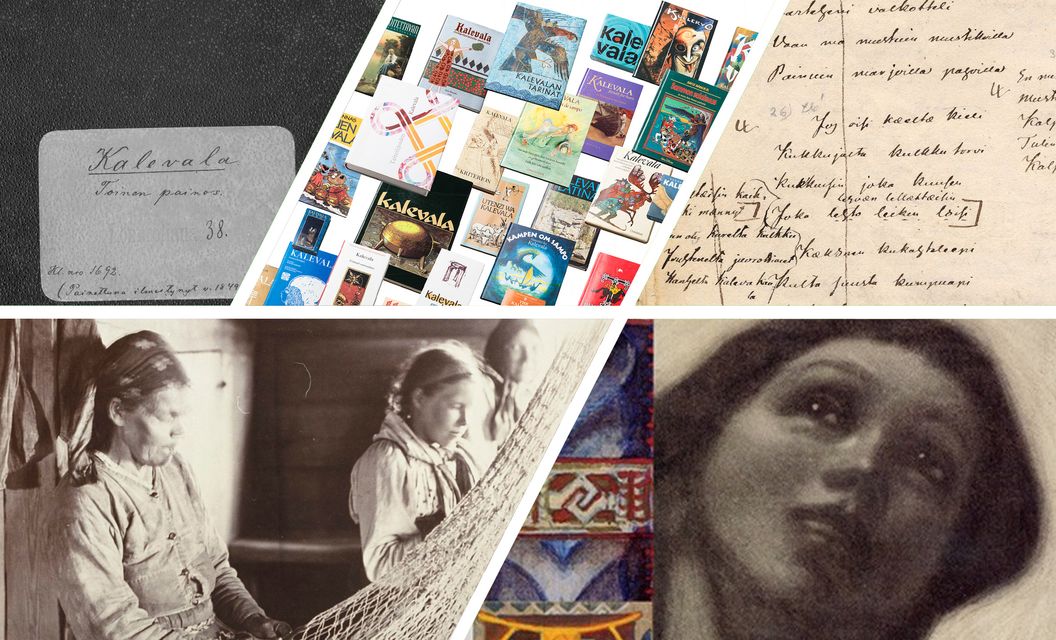

The Kalevala – what is it?

The Kalevala is the national epic of the Finns and Karelians. It is the most translated work of Finnish literature and part of world literature. The Kalevala is also a multi-layered combination of different oral-literary materials, worlds and meanings, which is why it escapes a single definition and interpretation.

The first edition of the Kalevala was published in 1835. Elias Lönnrot compiled it from folk poetry recorded into notebooks in 1828–1834, during his several lenghty collection trips among poetry singers especially in the White Sea Karelian villages.

At the time of publication of the Kalevala, Finland was an autonomous grand duchy of Russia, and before that, until 1809, part of the Swedish Kingdom. Especially for Finnish intellectuals, the Kalevala became a symbol of the Finnish past, Finnishness, the Finnish language and Finnish culture, a foundation on which they started to build the fragile Finnish identity. It also aroused much interest abroad, and brought a small, unknown people to the awareness of other Europeans.

Image: Johan Blackstadius, ”Väinämöinen Attaches Strings to his Kantele”, 1851. This is the oldest fine arts depiction of Väinämöinen.

What was Elias Lönnrot’s role in the birth of the Kalevala?

Elias Lönnrot (1802–1884) has been called a collector of fragmented epics, a collector of folk poetry, a scribe, a creative poet, and a singer. In reality, the Kalevala is Lönnrot’s epic poem and a 19th-century work of art, although its sources are deep in the folk traditions. Lönnrot created the epic by combining a variety of folk poems from different times. The Finnish-Karelian-Ingrian poetic culture did not contain a single epic whole, although for their length, some of the poems can be seen as miniature epics.

Image: Elias Lönnrot with his daughters. Detail from a family portrait, 1864. Finna.fi

The Kalevala is Lönnrot's epic poem and a 19th-century work of art, although its sources are deep in the folk traditions.

Lönnrot’s aim was to present folk poems and their meanings to the educated elite, who often had little knowledge of the Finnish language and the culture of the people across the eastern border. The literary challenge was to find ways to present the Karelian and Ingrian poetry and poetic tradition in a form that the urban readers could understand, while remaining as faithful as possible to the traditions.

Elias Lönnrot was well equipped to manage this unification work. He was the fourth of the nine children of a poor tailor and his wife in the rural Finnish speaking village of Sammatti, but through his formal education he rose to the Swedish speaking, pro-Finnish intelligentsia emerging at the time. On the other hand, practicing the medical profession–he was the district doctor of Kajaani for 30 years–and numerous trips to the remote villages of Finland and Karelia, collecting folk poetry, brought Lönnrot closer to the Finnish-speaking population, a people that he sought to enlighten in many ways.