Finland’s national epic, the Kalevala, rarely gets top billing when Japanese readers chat about “Nordic literature.” Hans Andersen and Henrik Ibsen usually go first. Yet the Kalevala has enjoyed nearly a century of reception in Japan – shaped not only by translations and scholarship but also by classrooms, children’s books, concerts, and even cultural diplomacy. This blog recounts the story: how the epic arrived, who championed it, which images of Finland it helped shape, and how those images evolved.

Power of Words

Japan’s earliest sustained contact with the Kalevala came via Lafcadio Hearn (known as Japanese name Koizumi Yakumo, 1850–1904). Born in Greece to British/Irish parents, Hearn moved to Japan in 1890. He taught English in many places in Japan and held the chair of English Literature at Tokyo Imperial University from 1896 to 1903. Known domestically as a collector of legends and ghost stories and as a mediator of Japanese culture to the West, Hearn’s writings were translated into Japanese and issued as collected works from 1926, including his Kalevala-derived pieces.

Hearn framed the poem around the power of words – verbal magic, shamanic incantation – arguing that while many northern epics pivot on warfare, the Finnish poem overflows with praise of nature and quiet life. This reading of a “peaceful epic” became a persistent motif in Japan’s reception of the work.

Cultural diplomacy

Takeo Matsumura (1883–1969) helped the Kalevala “land” in Japan. Although he later became a leading mythologist, his early career centered on English teaching, as mythology was still in its infancy in Japan’s academy. After comparative work on Japanese and Greek myths, he turned to Finnish materials. Matsumura’s work anchored the Kalevala as a world myth within Japanese intellectual life. In Shinwagaku ronkou (Studies in Mythology) (1929), he placed the poem within comparative mythology and proposed a durable interpretive frame: heroes who are craftsmen and herdsmen rather than kings; victory through song instead of force; a less hierarchical pantheon; and a geography defined by the tension between Väinölä (Finland) and Pohjola (Lapland). Matsumura’s work anchored the Kalevala as a world myth in Japanese intellectual life.

The 1930s added a new engine: cultural diplomacy. Finland’s first envoy to Japan, Gustaf J. Ramstedt (1873–1950; in office 1920–1929), introduced Finnish studies and the Kalevala to university audiences and the public. The famous folklorist Kunio Yanagita (1875–1962), the father of Japanese folklore, was one scholar with whom Ramstedt interacted. Ramstedt lectured at Tokyo Imperial University on the Finnish Literature Society, and encouraged to the study of dialects. Ramstedt also significantly influenced Kakutan Morimoto, who became the translator of the first complete Kalevala translation. He urged Japanese audiences to learn from a peaceable model of patriotism grounded in culture rather than conquest. Around the same time, the Finnish School in folklore methodology spread in Japan via Kaarle Krohn’s Minzokugaku houhouron (Folklore Methodology) (trans. by Seki Keigo, 1940).

The photo of The Kalevala Centennial Jubilee in the Embassy of Finland in Tokyo

The man in a kimono, second from the left in the front row, is Kakutan Morimoto.

Source: Karewara: finrando kokumintekijojishi 1937. Tokyo: Nihonshoso.

The First Full Translation, Children’s Adaptations, and Postwar Classic Status

The Kalevala Centennial Jubilee in 1935, organized by Finnish envoy Hugo Valvanne, brought unprecedented public attention. Radio broadcasts amplified interest, and on February 28th 1935, Morimoto presented the Kalevala in Asahi Shimbun(the Asahi Newspaper) alongside the Iliad and the Nibelungenlied. His 1937 full translation, Finrando kokuminteki jojishi Karewara (The Finnish National Epic Kalevala), distilled the epic’s ethos: “wisdom surpasses the sword, and song surpasses strength”. This reinforced a Japanese image of Finland as a land of peaceful rural culture. Morimoto also highlighted Sibelius and his Kalevala-inspired works; a pocket edition followed in 1939.

In 1940, Yasuko Morimoto (Kakutan’s wife) published a children’s version that adapted sensitive episodes, such as incest motifs, to the moral climate of the time. Yasuko also invented original parts of stories that fit the patriarchal context in Japan. Amid wartime constraints, Yasuko issued Mahou no uta (The Song of Magic, 1943). The advertisement introduced Finland as “Fighting bravely against the Soviet Union” and stated, “There are many beautiful stories handed down from generations in deep snow.” This advertisement reflected the political situation at the time.

After the war, juvenile retellings entered school readers and youth classics series, often adding moral inflections: in one version, Aino’s death becomes a lesson on obedience, and the oak is labeled “the devil’s tree.”

In postwar Japan, the Kalevala settled into a dual role as juvenile literature and a world classic. A fifth- and sixth-grade reader published in 1951 retold Rune 2 of the Kalevala almost faithfully but added a clear moral line, warning that the giant oak is “the devil’s tree” that must be cut down at once, while a 1955 collection of world classics for children retold Aino’s story with only minor plot shifts. A large multi-volume collection of world literary masterpieces for boys and girls issued between 1964 and 1968 placed a retelling of Väinämöinen’s story in its first volume alongside tales comparable to those found in the Arabian Nights and Greek Myths. In his commentary, Michio Namekawa characterized the work as “farmers’ literature” shaped by northern nature and linked its cosmogony to echoes in Japan’s oldest surviving chronicle, compiled in the early 8th century.

A then-popular theory of Ural-Altaic linguistic kinship (promoted by scholars like Imaoka Jun’ichirō) amplified affinities between Japan and Finland. The epic was often read as a peace-leaning classic that supported postwar democratization.

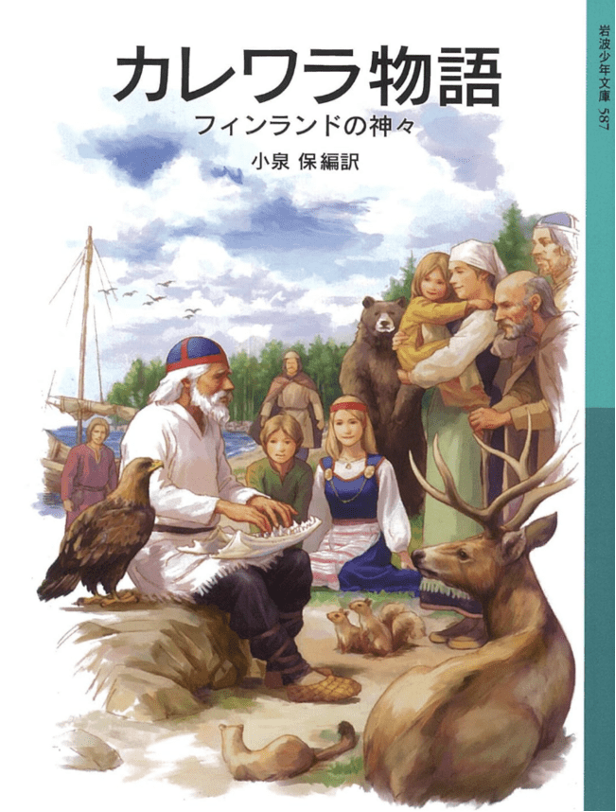

A major milestone came with Tamotsu Koizumi’s complete translation (1976), which standardized terminology and cadence and became the scholarly and educational reference. Koizumi continued to engage the Kalevala comparatively, translating Kai Laitinen’s Literature of Finland (1985) in 1993 and publishing a comparative study of the Kalevala and Japanese mythology in 1999. His 2008 juvenile Kalevala story retained challenging material such as the Kullervo episode and framed the epic as both Finland’s ultimate classic and a world cultural treasure.

Closing Thoughts

The Kalevala in Japan is a story of bridges: between lecture halls and living rooms, diplomacy and pedagogy, music and myth. Over the course of a century, the epic helped many readers envision Finland not as a distant curiosity, but as a community defined by peace, words, nature, and craftsmanship. That image – rooted in translations, classrooms, and concerts – still invites fresh readings today, whether you come for the enchanted oak, the heat and hiss of sauna, or the quiet conviction that language itself can make worlds.

More about the Author

Professor Yuko Ishino (Kokushikan University in Tokyo) first became interested in the Kalevala and began studying Finnish history when she spent a year on a homestay in Haapavesi in 1995–96. Her doctoral dissertation examined Greater Finland ideology and Kalevala studies (published in Japanese in 2012 by Iwanami Shoten as The Birth and Transformations of “Greater Finland” Thought: The Epic Kalevala and the Intellectuals). She has authored numerous books and articles on the history of Finland and published an introductory history of Finland in 2017. She is a member of the Kalevala Society and a corresponding member of the Finnish Literature Society (SKS). From April 2024 to March 2025, she served as a visiting researcher at University of Helsinki.

Images

- The photo of The Kalevala Centennial Jubilee in the Embassy of Finland in Tokyo

The man in a kimono, second from the left in the front row, is Kakutan Morimoto.

Source: Karewara: finrando kokumintekijojishi 1937. Tokyo: Nihonshoso. -

Source: Morimoto, Yasuko 1940. Karewaramonogatari: shounen shoujo no monogatari, Tokyo: Kyozaisha.

-

Source: Tamotsu Koizumi, Karewara Monogatari: Finrando no kamigami published in 2008, illustrated by Kentaro Kawashima.