The Kalevala: Introduction

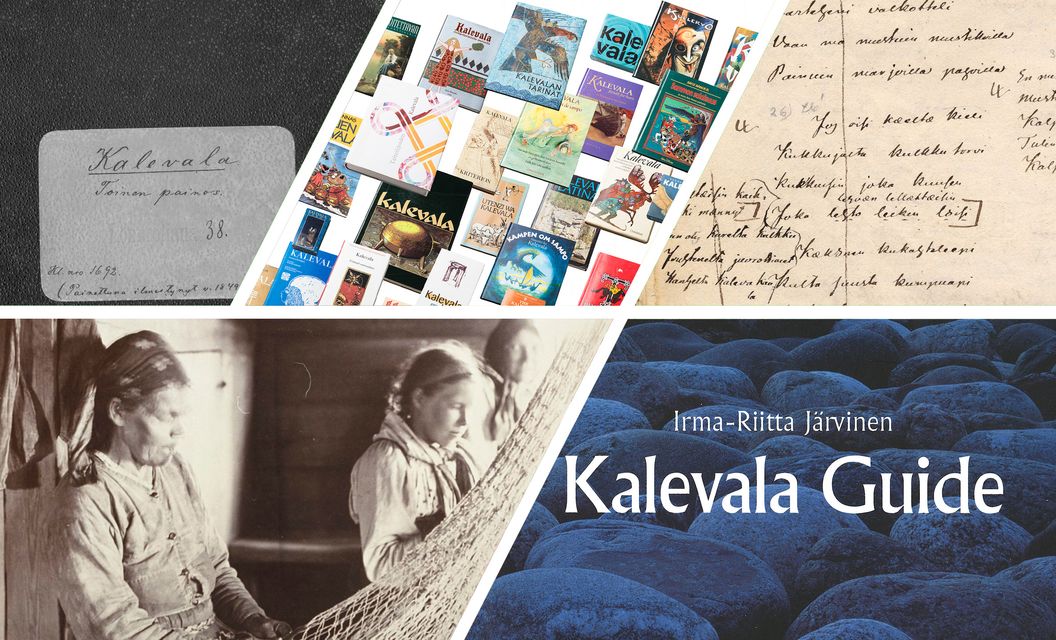

The Kalevala (1835, 1849), by Elias Lönnrot, is probably the best known and certainly the most widely translated work of Finnish literature. The work’s enduring popularity raises an interesting question: how is it possible that this book, honoured by the solemn epithet ‘the national epic of the Finns’, continues to fuel the creative imagination? What is it about the Kalevala that keeps on attracting and inspiring new generations of readers and artists?

The world of the Kalevala is mythical – not historical. Therefore, its stories cannot be connected to actual places or events. Essentially, it lives in the realm of the mind’s eye. Lauri Honko, a Finnish scholar of the Kalevala, writes: ‘Many of the stories and their details become easier to understand if we do not try to force them onto the level of historical time and everyday experiences but try to listen to the voice of myth as it speaks to the man who conceives time as mythical.’

The ‘heroes’ of the Kalevala are profoundly human in their behaviour and weaknesses. Kai Nieminen, a poet who has retold the Kalevala in present-day Finnish (1999), explained his experience of the epic: ‘Lönnrot’s Kalevala is not pompous and holy; it is funny, exuberant, full of joys and sorrows, smiles, teasing, hidden irony, politics and lyrics.’

For a long time, a misconception prevailed among the public in Finland about the Kalevala and its relation to folk poetry. This is called ‘the romantic conception’ – the idea that the Kalevala was a shattered epic, whose scattered fragments were later simply collected from the mouths of the people and put into a book. While it is true that the Kalevala is firmly based on folk poetry, the work is the result of the conscious efforts of its writer, Elias Lönnrot. He devised the plot, built the story and created a set of compelling characters. The amazing thing is that Lönnrot, who collected the poems from the singers, learnt the language of folk poetry so well that he thought of himself as one of them:

‘I became a singer myself.’

With the Kalevala Elias Lönnrot sought to paint a picture of Finland, in which the era of heroes, shamans and magic is coming to an end and the new Christian era is beginning. He was determined to create a history for the Finns, a people whose literate culture was still in an early phase of development, and whose knowledge about the past was vague. Thus, the Kalevala gradually came to have an immense impact on the development of a Finnish nation al identity, which means that it later had political significance, contributing to the establishment of an independent nation (1917). Now Finnish culture could clearly stand apart from that of Sweden and of Russia. Nowadays, the issue of national identity is no longer in the foreground – because it already has been fully acknowledged. Today, the Kalevala is more compelling as a literary work that can inspire and challenge artists, writers, musicians and scholars in Finland and beyond.

Artistic interest in the Kalevala has waxed and waned over the decades. After the Second World War, there was a fairly long period of relative indifference to the epic, but interest gradually revived during the 1970s. Artists working in various mediums are currently drawing their inspiration from the Kalevala. It keeps on emerging in new modes of expression: in modern dance and theatre, in rock music, jazz, in comics and children’s books.

The language of the Kalevala is varied and rich. It is based on the eastern (Karelian) dialects of Finnish. Although the sentence structures are clear, the vocabulary poses a challenge to present-day readers, for the world of the Kalevala seems so removed from our own. Fortunately, ‘Kalevala dictionaries’ help to understand the archaic or simply alien language of the epic.

The Kalevala has come to be woven into the fabric of modern Finnish cultural life and even business since the end of the nineteenth century. There are the insurance companies Ilmarinen, Tapiola, Pohjola and Sampo (also a bank), not to mention a newspaper called Kaleva and an asphalting company named Lemminkäinen. The name Sampo is also associated with an icebreaker, a harvester and serves as a trademark for matches. Kalevala Koru produces high quality jewellery and Väinämöinen’s Coat Buttons are tasty rye crisps. Names from the Kalevala are commonly used as first names (e.g. Väinö, Sampo, Seppo and Ilmari for males, Aino, Marjatta, Annikki and Kyllikki for females) and place names (e.g. Tapiola, Metsola).

Elias Lönnrot signed the preface to the Kalevala on February 28, 1835. This day has been commemorated as Kalevala Day and the Day of Finnish Culture for one hundred years. After the first edition of the Kalevala, a new, more expansive version was published in 1849; this is the book that is usually referred to when we speak about the Kalevala.